Species | Species Profiles | Red Squirrel

There are two species of squirrel currently in Ireland. The red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) is a native species that has been present since before the last ice age.

It is totally dependent on woodland as a habitat, and through deforestation has suffered a number of troughs, including almost complete extinction in the 17th century. The current population mainly derives from reintroductions that took place in a number of locations during the 19th century. The second squirrel species is the American grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) that was introduced on just one occasion in 1911 to Co. Longford. The establishment and subsequent spread of this alien species has resulted in competition with the red squirrel for food resources, with the red squirrel invariably losing out to the grey.

Red squirrels are distinctly smaller, weighing approximately half that of a grey squirrel. Reds can be distinguished from greys by their long ear tufts and fur colour, although grey squirrels can be a brown-red colour in the summer, and reds sometimes taking on a greyish hue in the winter, leading to some confusion. Red squirrels spend the majority of their foraging time in the tree canopy, whereas greys feed more frequently on the ground. Red squirrels are particularly elusive, often hiding against the opposite side of the tree trunk from intruders, whereas the brash grey squirrels display less wariness of humans.

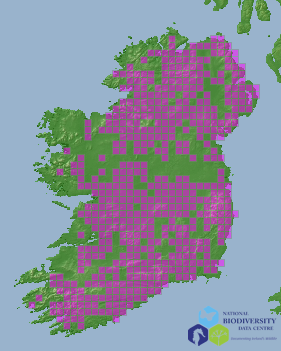

Distribution

The red squirrel is still widespread throughout the island of Ireland, although its distribution can be quite patchy. The grey squirrel has spread through the eastern half of the country, and in certain midland areas where the grey has been longest established, red squirrels have disappeared. Greys continue to spread to the northwest and southwest, but moves to the west of Ireland have been halted by unsuitable terrain, with the River Shannon delineating the western extreme of their distribution. Red squirrels continue to disappear from forests into which the grey squirrels have invaded, and there has been a 20% decline in their range in the one hundred years since the grey squirrel arrived, with half of that decline occurring in the last ten years.

Nests

Squirrels nest in dreys, which are round structures built of sticks and foliage against the trunks of trees. Dreys can also be built in hollows in trees, or nested within heavy ivy, making drey counts (an indirect method of determining squirrel abundance in an area) very difficult to do with any accuracy. A single squirrel will use a number of dreys at a time, and the dreys will be shared with other individuals. Squirrels are not territorial, although each animal will have a preferred area within their home range which may be defended from other individuals according to a linear social hierarchy.

Life Cycle

Breeding usually begins in January or February, with males chasing females, and the most dominant individuals being most successful. After a gestation period of five to six weeks, the female gives birth to a litter of one to six kittens, with three being the usual litter size. The young are born blind and naked, and are not fully weaned until approximately seven to ten weeks after birth. Maternal behaviour can continue though for some time, with young animals only resembling adults at three months of age.

The onset of the breeding season in any year is determined by the seed crop available to the squirrels in the previous autumn. In good seed years breeding can begin quite early, leaving the females with enough time to wean the first litter, and produce a second litter in early summer. Poorer autumnal seed crops invariably mean breeding females will only produce one litter in each breeding season. Young animals will disperse in the autumn if they were born in a relatively early litter, but summer born litters will remain in their natal woodlands over winter and disperse the following spring. Young squirrels will breed for the first time at about 13 months old, and breeding success improves as the animal ages, with older females more likely to produce second litters each year, and older males more likely to win a breeding chase. Mortality is highest in young animals, with 50–70% of young not making it to breeding age. Survival subsequently is better; some squirrels live to six years of age, and even longer in captivity.

Foraging

Red squirrels feed mainly on tree seeds, although they can utilise fungi, fruit and buds as they become available in the woodland. Grey squirrels have a broader diet, making greater use of alternative food sources and also including grain, flowers, eggs and tree bark in their diet. Both species depend predominantly on nuts and seeds though, hence the fierce competition between them.

Conservation Status

Although there is no direct aggression between the two species, there is severe competition for shared food resources, with the grey squirrel usually the victor. Red squirrels can be successful in all woodland habitats, and are even seen in higher densities in broadleaved and mixed forests; however, when the grey arrives to a broadleaved wood the red will disappear, usually within 20 years. Red squirrels can survive however in coniferous woods, which do not provide enough food resources for the larger greys. However, even a small amount of broadleaved habitat in the vicinity can tip the balance towards the grey squirrel once more. The demise of the red squirrel is further exacerbated by a disease, squirrel pox virus, which is almost always fatal. The disease manifests itself through lesions to the face and hands of the animals, particularly around the eyes. The squirrel usually goes blind and perishes within a couple of weeks of infection. Squirrel pox virus is believed to have been brought in to the country and spread by the grey squirrel, who acts as a carrier of the virus, but is never mortally affected. The squirrel pox virus has been linked to the accelerated loss of red squirrels in Great Britain, and was first identified as being present in Ireland in the last couple of years.

The red squirrel is protected under the Wildlife Act (1976) and Wildlife (Amendment) Acts (2000 & 2010) and the Bern Convention (Appendix III). It is not afforded stronger protection globally, as it is still very successful throughout most of its range, which stretches across Europe and Asia. Grey squirrels have recently been introduced to Italy, and this new threat to the European populations of red squirrel may increase their conservation status in years to come.

Grey squirrels also cause a lot of damage to Irish woodland through their habit of stripping bark from trees. The outer bark is discarded and the soft sappy tissue exposed beneath is then scraped away by the squirrel. This can cause a loss in timber quality and value, and where the bark stripping extends around the tree’s circumference, the death of the tree. This damage affects some species of tree (for example beech and sycamore) more than others, with the squirrels selecting the trees to scrape according to the ease of removal of the bark, and the rewards offered. The damage is most frequently seen in the spring, and on young pole stage trees.

Colin Lawton

Colin Lawton first started working on squirrel ecology while studying for his PhD in Trinity College Dublin in the 1990s. Since moving to his current position as mammal ecology lecturer in NUI Galway, he has continued to research both squirrel species, looking at the spread of greys and the current status and conservation of red squirrels.

Selected Publications and Reports

- Lawton C., Hanniffy, R., Molloy, V., Guilfoyle, C., Stinson, M. & Reilly, E. (2020) All-Ireland Squirrel and Pine Marten Survey 2019. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 121. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Ireland. https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/IWM121.pdf

- Flaherty, M. & Lawton, C. (2019). The regional demise of a non-native invasive species: the decline of grey squirrels in Ireland. Biological Invasions, 1-16.

- Goldstein, E.A., Lawton, C., Sheehy, E. & Butler, F. (2014). Locating species range frontiers: a cost and efficiency comparison of citizen science and hair-tube survey methods for use in tracking an invasive squirrel. Wildlife Research 41, 64-75.

- Sheehy, E. & Lawton, C. (2014). Population crash in an invasive species following the recovery of a native predator: the case of the American grey squirrel and the European pine marten in Ireland. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23 (3), 753-774.

- Waters, C. & Lawton, C. (2011). Red Squirrel Translocation in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 51. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland.

- Lawton, C., Cowan, P., Bertolino, S., Lurz, P.W.W. & Peters, A.R. (2010). Consequences of introduction of non-indigenous species: two case studies, the grey squirrel in Europe and the brushtail possum in New Zealand, OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) Scientific and Technical Review, 29 (2), August 2010: 287-298.

- Finnegan, L.A., Poole, A., Lawton, C. & Rochford J. (2009). Morphological diversity of the red squirrel Sciurus vulgaris in Ireland. European Journal of Wildlife Research 55 (2), 145-151.

- Poole, A. & Lawton, C. (2009). The translocation and post release settlement of red squirrelsSciurus vulgaris to a previously uninhabited woodland. Biodiversity and Conservation, 18, 3205-3218.

- Lawton, C. & Rochford, J. (2007). The recovery of grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) populations after intensive control programmes. Biology and Environment 107 (1), 19-29.

- Carey, M., Hamilton, G., Poole, A. & Lawton, C. (2007). The Irish Squirrel Survey 2007. COFORD, Dublin.

Key information

English name:Red Squirrel

Latin name:Sciurus vulgaris

Irish name:Iora rua

Identifying feature:Large bushy tail, ear tufts, red fur (usually)

Number of young:1-6 kits (usually 3) born in spring

Diet:Seeds and nuts of various trees

Habitat:Woodland. Population density varies with habitat, Hazel, beech and Scots pine preferred